Search

Making Informed Food Security Decisions with Planet

With the COP28 conference in Dubai running from November to December 2023, world leaders need to understand the landscape of food security globally. Data from Planet and Planet’s partners empowers them to make informed decisions to help those in need around the world.

A set of Planet SkySat images showing the destruction of a grain elevator near Rubizhne, Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine. Before image: April 8, 2022. After image: April 21, 2022.

In early June this year, a dam on the Dnipro River collapsed, causing massive flooding and triggering evacuations downstream. Located in a contentious area along the conflict’s frontline in Ukraine, the “destruction of the Kakhovka Dam earlier this year drained a massive reservoir and left nearly a thousand miles of irrigation channels without a source of water,” according to NPR. Notwithstanding the strategic effects, this collapse compounded stress on Ukrainian agriculture, which was already operating at a reduced capacity due to the conflict, as many farmers along the frontlines and elsewhere had been unable to plant their crops. But how can we understand where exactly the trouble spots are? And how can we measure the effects, both in terms of the amount of unused cropland but also in terms of the financial ramifications for Ukrainian farmers? And how does this all affect food security globally? Satellite imagery from Planet can help answer those questions.

SkySat imagery of the Kakhovka Dam.

The before imagery (left) was captured on June 4, 2023, and the after imagery (right) was captured on June 6, 2023.

Stories informed by Planet's Kakhovka Dam Imagery

Prior to the dam collapse, Ukrainian farmers had already been affected by war in numerous ways. For example, approximately 240 miles northeast of the dam, it had been a little over a year since two Ukrainian farms had been attacked. The set of images below shows how one agricultural area around the village of Dovhenke, in Kharkiv Oblast, was affected after two area farms had been destroyed.

Three PlanetScope images of the area around Dovhenke.

Two farms were destroyed (annotated by white boxes), and both of the resulting craters each measured between approximately 40 and 50 meters in diameter. The images were captured on June 21, 2021, June 10, 2022, and June 14, 2022, respectively.

The first image in the set above shows what the area looked like in June of 2021 — before the Russian full-scale invasion in February of 2022. However, in the following two images above, both taken in June of 2022, you can see that two farms were directly hit. Battle damage is also observed in the fields throughout the June 2022 images. Each of the craters seen in the areas where the farm buildings once stood measured approximately 40-50 meters in diameter.

Sentinel-2 satellite imagery, shown below, indicates that the farms were destroyed between May 8, 2022, and May 13, 2022. This time window is corroborated by an April 2023 PAX and Centre for Information Resilience report, which referenced a Twitter image posted on May 11, 2022, depicting a large plume of smoke allegedly showing the same area. The imagery below depicts the northern farm.

Sentinel-2 true color imagery of the northern farm near Dovhenke.

The imagery seen here shows before (May 8, 2022) and after (May 13, 2022) the attack. Source: Sentinel Hub

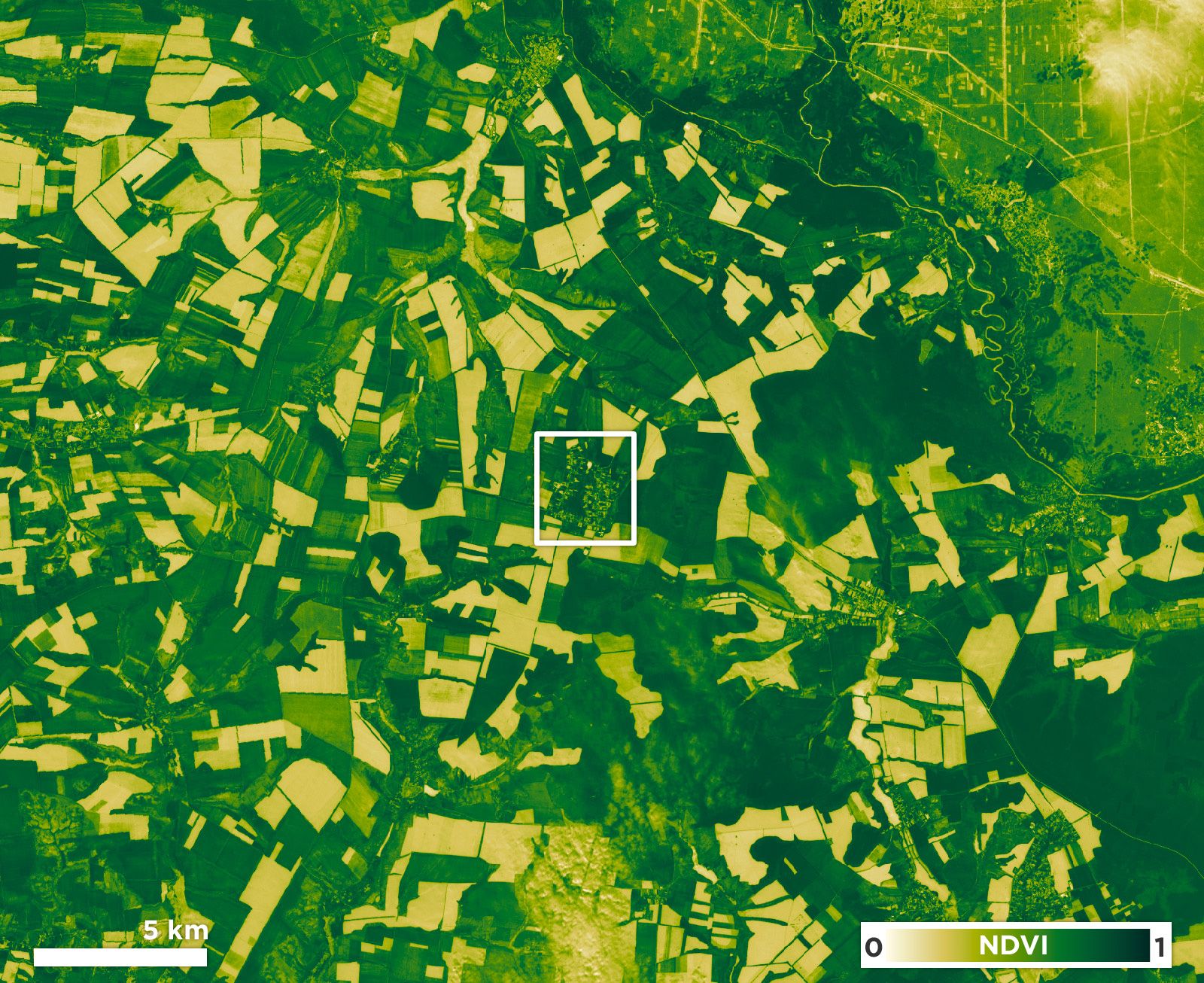

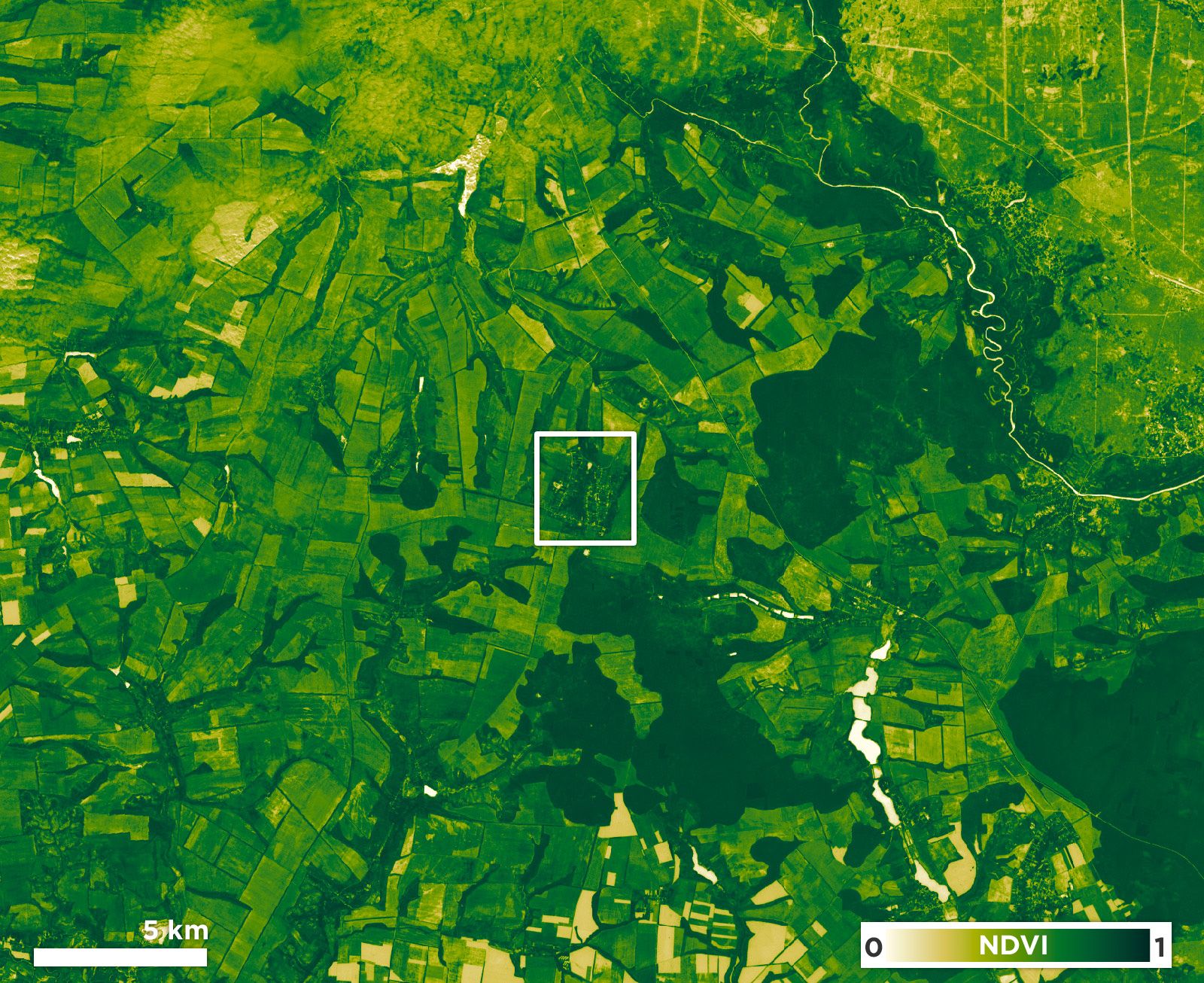

Sentinel-2 NDVI imagery of the northern farm near Dovhenke.

The imagery seen here shows before (May 8, 2022) and after (May 13, 2022) the attack. Source: Sentinel Hub

A SkySat image captured on June 28, 2022, depicting the northern farm near Dovhenke.

The image shows an approximately 40-meter crater where a farm building once stood.

The potential aftereffects of the attacks can be visualized using Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, or NDVI, which “is used to quantify vegetation greenness and is useful in understanding vegetation density and assessing changes in plant health,” according to the USGS. The below imagery compares NDVI values in the area between May of 2021 and May of 2023, displaying a decrease in farming activity in this region.

Sentinel-2 NDVI imagery depicting the area around Dovhenke.

The before imagery (left) captured on May 23, 2021, depicts normal agricultural activity, while the after imagery (right) was captured on May 21, 2023, and depicts a marked decrease in agricultural activity in the area around Dovhenke. Source: Sentinel Hub

The difficulties that Ukrainian farmers are facing represent a larger problem of food insecurity worldwide, which experts interviewed by Planet say is presently at a highly concerning level. More than 4 out of every 10 people in the world (approximately 3.1B people) cannot afford the cheapest form of a healthy diet, according to Caitlin Welsh, director of the Global Food and Water Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. And, according to the World Food Programme (WFP), approximately 47 million people across 54 countries are in "emergency" or worse levels of hunger. Countries like Yemen, Sudan, South Sudan, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Somalia are especially vulnerable to food insecurity and rely on aid from the world community to keep their populations alive.

Moreover, recent data published for October 2023 by the Famine Early Warning Systems Network showed that Burkina Faso and South Sudan were both at risk of famine. The report also stated that over half of the populations of Yemen and South Sudan will most likely need humanitarian food assistance. Overall, the total number of people facing food insecurity globally rose to a record high last year, according to the WFP.

The Russo-Ukrainian conflict has also exacerbated world food supplies, as wheat and corn production levels there are falling below pre-full-scale invasion levels. World leaders need to know what is happening in places where access to the ground is either restricted, such as in conflict zones, or limited or impossible, such as after natural disasters, such as flooding and earthquakes.

Planet satellite imagery can help world leaders understand the problems on the ground to help them make more well-informed decisions about where to focus resources and how to help the most vulnerable. Planet’s partnership with NASA Harvest, NASA’s global food security and agriculture consortium, has given the world key agricultural health data to work with.

“Today, we are facing unprecedented food insecurity around the world. And in order to be able to address this challenge, we’ve got to be able to look at the evidence basis,” said Dr. Inbal Becker-Reshef, Program Director of NASA Harvest. “And that means that oftentimes satellite data is your only way to monitor the impact of that and ultimately help to inform decisions — whether that’s disaster risk financing; whether that’s mobilizing humanitarian aid; whether that’s providing information on big production export countries where there isn’t as much transparency in understanding what their production might be and they can have a big influence on our global food system and ultimately global food security.”

Our biggest evolution with our partnership with Planet came when the war in Ukraine started and we recognized we needed to move very quickly in order to be able to inform decisions and inform information on what was happening across the agricultural fields in Ukraine, in particular in the occupied territories where there was no information that was coming from those areas.

Dr. Inbal Becker-Reshef, Ph.D.

Program Director, NASA Harvest

In an interview with NPR, Dr. Becker-Reshef said that “between 6.5 and 8.5% of Ukraine's total cropland [...] has been abandoned.” An estimated 25 million people could have been fed with the land that has gone out of production due to the conflict. And even if Ukraine is able to push back Russian advances and regain access to this land, planting crops will be difficult, if not impossible, due to the damage caused by artillery shelling, mortars, and air-delivered munitions, as well as concerns about landmines and contamination of the crops due to the usage of these weapons. “The fields are mined [with] a large number of shells that did not explode, and this is a very big problem,” Serhiy Leonov, co-founder of Ukrainian agriculture business Rovy Agro, said during an Atlantic Council event. “About 470,000 hectares of arable land have been mined in Ukraine, [and] demining [would take] about 10 years,” he said.

Ukrainian cropland is vital to maintaining wheat production levels globally. According to Production, Supply, and Distribution (PSD) data from USDA, wheat production in Ukraine, widely known as the breadbasket of Europe, remains at about 30% below pre-full-scale invasion levels. Dr. Becker-Reshef said she estimates that Ukrainian farmers lost about $2B USD this year alone due to the conflict.

But the effects of the conflict go beyond Ukraine’s borders: the conflict has affected the global food market and, by extension, global food security. Many of the countries listed above rely on imports, such as wheat from Ukraine, to feed their populations in need. According to Dr. Joseph Glauber, a Senior Adviser in the Global Food and Water Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), “global [wheat] exports were off about 7% from 2021 and global ending stocks (excluding China) were at lowest level as a percent of use since 2007/2008. Wheat prices have fallen to below pre-war levels, but because stocks have not rebuilt, price volatility remains high.”

SkySat imagery captured on June 28, 2022, depicting damage to fields located near Dibrivne, Kharkiv Oblast, Ukraine.

In order to understand the Russo-Ukrainian conflict’s effects on the country’s cropland, NASA Harvest uses Planet satellite imagery to conduct analyses, both at the crop field level and at the country level. Using Planet data, NASA Harvest assessed that much of the unplanted cropland in Ukraine falls along the front lines of the conflict.

PlanetScope mosaic from July 12-26, 2022, annotated by NASA.

Source: NASA

While access to Russian-occupied territory in Ukraine for journalists, non-governmental organizations, and intergovernmental organizations is limited, remote sensing provides a unique window into these areas. Using Planet data, NASA Harvest was able to examine croplands in the entirety of Ukraine, including occupied territories, and there is some good news. For example, while 2023 saw a slight decrease in planted area, due in large part to the conflict, the country saw overall higher yields due to good weather, according to NASA Harvest. It should be noted, however, that almost a quarter of Ukraine’s total wheat production came from the occupied territories.

Ukrainian farmers’ resilience has proven to be a boon not only to their country but also to global food markets in general. “[Ukraine has] continued to export a large amount of grain out of the country which has helped stabilize markets,” Dr. Becker-Reshef said. She continued: “We must continue to ensure that grain can move out of Ukraine in order to avoid significant price spikes.”

Planet data adds value in multiple ways: imagery can help inform research about grain shipments at ports, but it can also analyze how (and whether) cropland is being used across the country.

A Planet SkySat image captured on June 5, 2022, of a grain terminal in the port of Sevastopol in occupied Crimea.

Planet data contributes to food security research that is key to understanding how people around the world are affected by climate change, conflict, and global agriculture markets. “We’re facing unprecedented levels of food insecurity and getting further off track from the SDG Goal #2 of No Hunger,” Dr. Becker-Reshef said. “Increasing extreme weather events due to climate change are only exacerbating the situation; those suffering the most are those that have contributed the least. It is important that we have both the mechanisms to have data on these losses and to be able to inform programs that provide a safety net to ensure food security in spite of these losses,” she said.

A confluence of events, from extreme weather events to conflict, can create “shocks to the food system,” and there is a “great need for information” to fill knowledge gaps, according to Dr. Becker-Reshef. NASA Harvest’s rapid response program incorporates Planet data into their workflows to help them speak from an informed perspective, guiding thought on food security policies on the global stage.

Planet will continue to work with its partners, including NASA Harvest, to provide data contributing to the public good and to the understanding of the effects of conflict globally.

If you are an academic or non-profit organization seeking access to Planet imagery for research, use the form below to contact us.

Get in Touch with Planet

We love meeting people from around the world. Reach out so we can connect.

© 2025 Planet Labs PBC. All rights reserved.

| Privacy Policy | California Privacy Notice |California Do Not Sell

Your Privacy Choices | Cookie Notice | Terms of Use | Sitemap