Natasha Nogueira on High Altitude Balloons, Cubesats and Perseverance

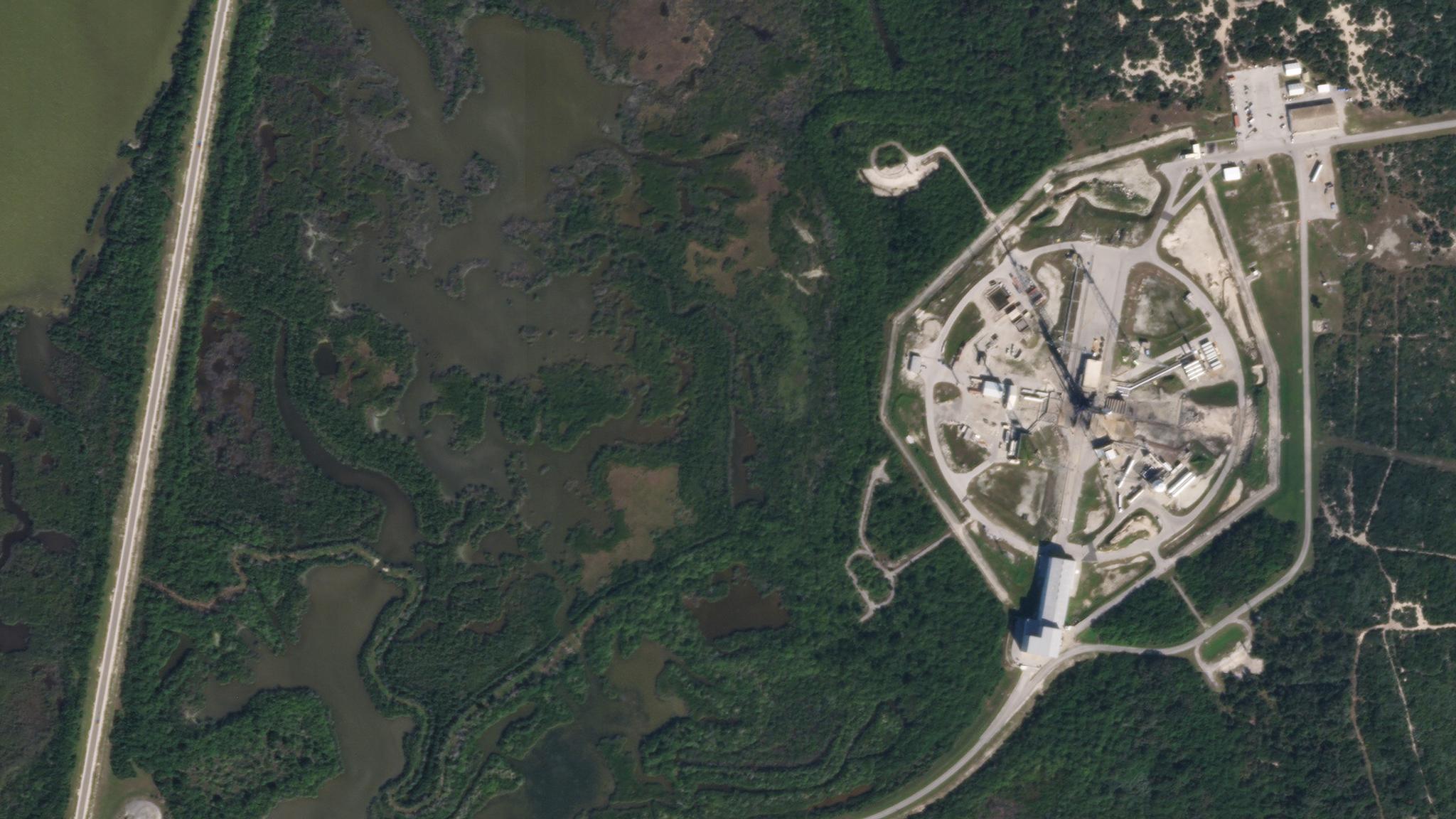

Space Launch Complex 40 at Kennedy Space Center, with a Falcon 9 on the pad. © 2020, Planet Labs Inc. All Rights Reserved.

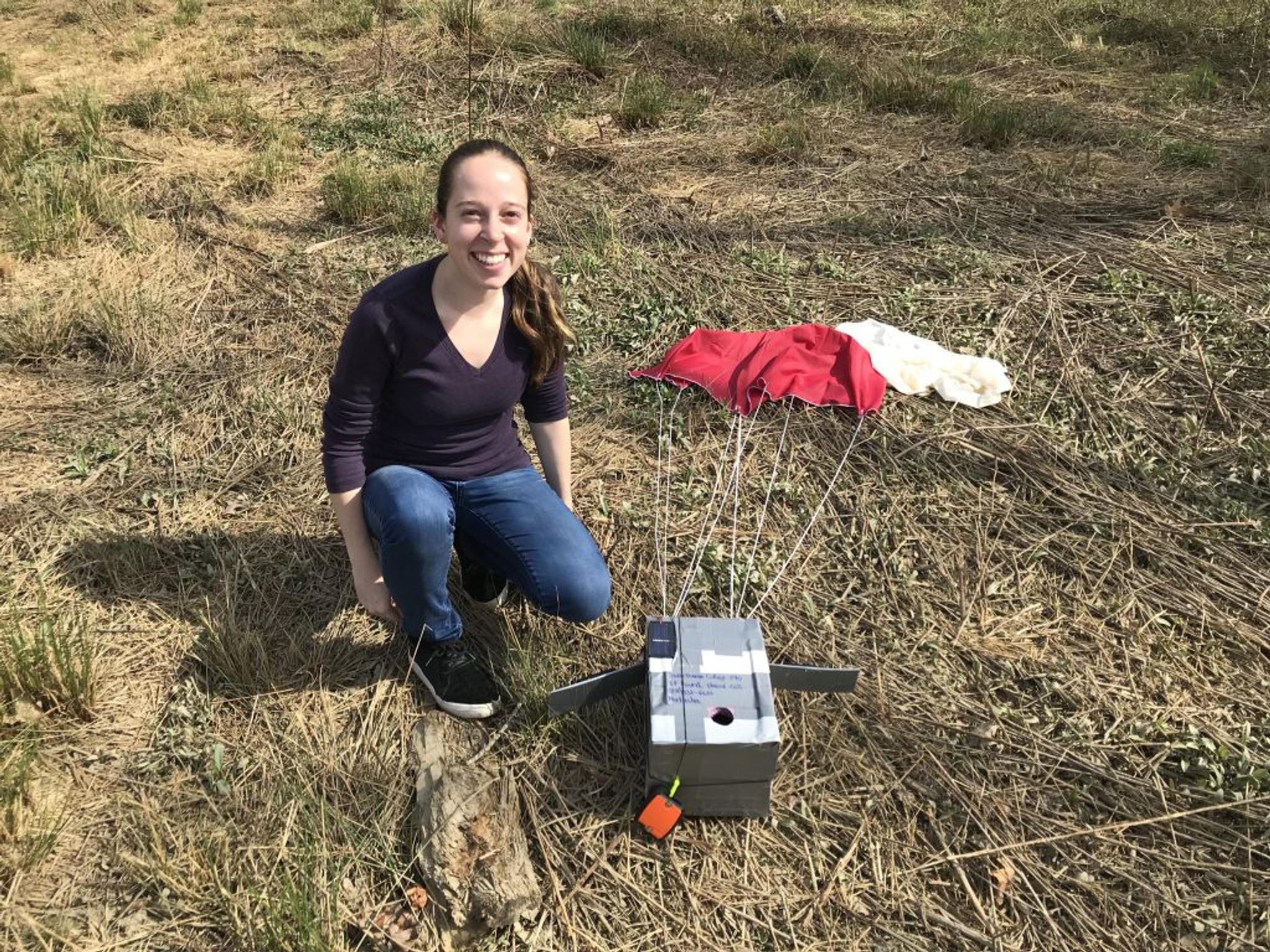

StoriesThis is the fourth installment in our Stellar Minds series, where we profile Planet’s extraordinary employees and their accomplishments. Keep checking our blog for upcoming features on some of the most remarkable people in aerospace today.This week, we’re talking to space systems engineer Natasha Nogueira, one of the stellar minds responsible for the success of our SkySats, including Skysats 19-21, launched yesterday. What is your role at Planet? I’m a Space Systems Engineer, my official title is Flight Operator, and I work on the SkySat Mission Operations team. Really most of what that entails is keeping the fleet of SkySats we have up-to-date, running smoothly and fixing any issues that come up. There’s a lot of different tasks I find myself working on, whether it's triaging why temperatures are looking odd on a spacecraft or correcting the sequences we use to command and control the spacecraft. I also spend quite a bit of time doing cross-team work interacting with the Flight Software team. When they have a new update for the SkySats, I’m the one who will run the updates from an operations perspective. While flight software ensures that the updates themselves are functional, I make sure that they are compatible with the spacecraft, conduct my own testing and create a plan for how we will execute the updates. My role ends up being a whirlwind of different things, which is really exciting! How has going remote and working from home affected your work? Going remote, interestingly enough, has not been super hard. I wouldn’t say I enjoy being remote, but my team is really well equipped to be working remotely. My team alternates shifts, and when we’re on shift, we're dedicating our time to operating and maintaining the satellites. These shifts run through the weekend as well, so most of us on the team are used to working from home. Can you describe a day, or shift, in the life of a Planet space systems engineer? Working on shift is really just taking care of the satellites. We’ll manage maintenance activities, updates to spacecraft and triage any anomalies that pop up. Today, I was fixing an issue we see sometimes with our SkySat’s sequences, which can control different satellite activities including imaging. Sometimes sequences get cancelled and when that happens, one of the heaters in the spacecraft gets turned off which may have been a necessary measure in the early days of the SkySats, but is actually counterproductive now. So what I was doing today was actually coming up with a new anomaly procedure that will detect when one of these sequence-abort faults happen and it’ll just turn the heaters back on. Another part of my daily work, which I was actually doing just before this, was testing. We have three testbeds in the data center in San Francisco—exact replicas of the hardware on the SkySats, but laid out on flat panels. We use those to test any updates or changes that will eventually go up onto the spacecrafts. And once I’ve done the testing, I usually send my work off to other team members to take a look before it actually gets implemented. Have you always wanted to be an aerospace engineer? For me, becoming an aerospace engineer felt like a slow process, but looking back, everything I did was always geared towards space and engineering. To start, the first internship I got in high school was actually at the Small Satellite Lab at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, run by former NASA astronaut Dr. James Newman. During that internship, I didn't get to work on the actual satellites, but I learned a lot about them and my main project was on high altitude balloons. I started as a member of the team designing and building the circuit board, and three years later (during a gap year after high school) I was the team lead overseeing two different High Altitude Balloon projects. We built these payloads that somewhat resembled a cubesat and conducted high altitude flights with these balloons, sending them up to 100,000 feet or what we call “near space.” By doing that, we were able to simulate a space environment without actually being in space, and this let us do a lot of testing on things like radio systems or hardware that ended up becoming a part of cubesats (which were later sent into space!). Dr. Newman was my boss and mentor, and the experiences I got in that lab combined with the mentorship from such an inspirational and kind scientist was what really led me to embrace space and want to go into the space industry. For a while, I wasn’t 100 percent sure if I wanted to do engineering or move more into astrophysics, because I did exciting astronomy research with young binary star systems in college, specifically analyzing protoplanetary disks. I’ve always been interested in space, how much we don’t know about it and the sense that everyone in the field is continually learning has always inspired me. Ultimately, I decided that I wanted to stick with engineering, but within the space context. So I ended up putting my two passions together and became an aerospace engineer. [caption id="attachment_145469" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Ready to Get Started

Connect with a member of our Sales team. We'll help you find the right products and pricing for your needs.